Our human family now has 8 billion members; this should be a reason to celebrate. It is a milestone representing historic advances for humanity in medicine, science, health, agriculture and education. More women survive pregnancy. More newborns make it through the precarious first months of life. Children are more likely to grow to adulthood and beyond, and people live longer, healthier lives.

Yet this milestone has been met with considerable anxiety. The world reaches and exceeds 8 billion people at a moment of overlapping and escalating crises, from the COVID-19 pandemic to the dawning climate catastrophe and historic levels of mass displacement. Weakened economies, conflict, and food and energy shortages pose threats everywhere in the world. The future can seem bleak; globally, more than 6 in 7 people say they feel insecure. Amid these concerns, it is all too easy to interpret the biggest demographic headlines of the moment – 8 billion people on Earth alongside historically low fertility rates in many countries – as signs of impending disaster.

To be sure, there are many valid and pressing concerns related to population, such as the complex links between population size, affluence and fossil fuel consumption, and the challenges of budgeting for infrastructure, health services and pension programmes. But when we treat populations as problems, rather than people, we obscure the very real issues we need to address.

To many, fertility rates that deviate from 2.1 children per woman are red flags. Higher fertility rates suggest a population “bomb”; lower rates suggest a population “bust”. From these perspectives, both the problem and solution start to take the shape of a woman’s body: Climate crisis? Convince women to have fewer children. Ageing societies? Convince women to have more children. In this way, women’s and girls’ bodies are treated as instruments to enact population ideals, a notion made possible by their still subordinate status, socially, politically and economically.

There is a long history of states, policymakers and others manipulating population numbers to favour some groups and discriminate against others. Women have paid the heaviest price, their bodies treated as the “tool” for adjusting population numbers judged to be too “high” or too “low”. History also shows us that these efforts, by and large, do not produce their desired effect.

It is time for a new approach, a new vision of population that puts people at its centre. It is time to put aside fear, to turn away from population targets and towards demographic resilience – an ability to adapt to fluctuations in population growth and fertility rate, which have taken place throughout history and will continue to take place. This means investing in data collection that looks at, and beyond, population sums and fertility rates. It means asking the right questions, such as whether people are able to meet their fertility goals.

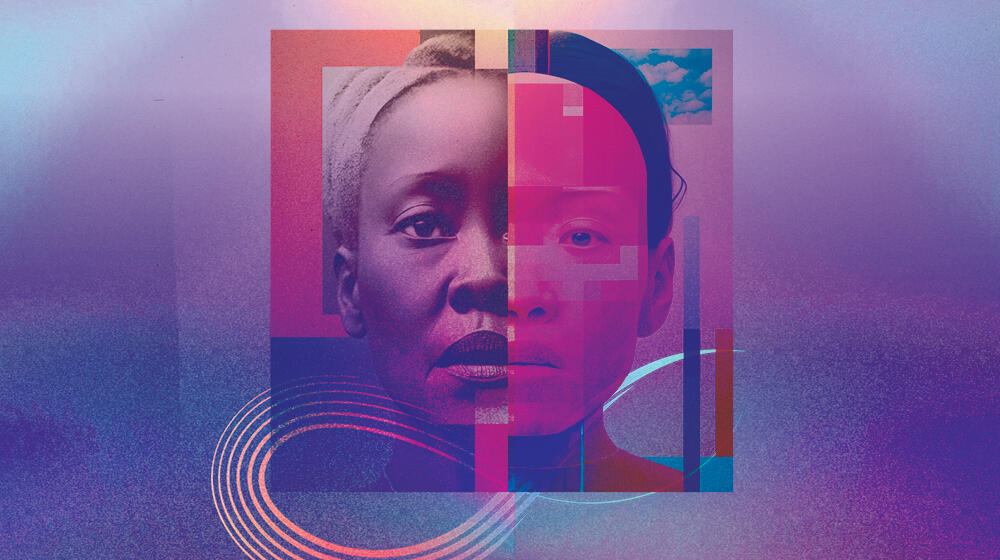

Societies can become more resilient with policies that support sustainable development and human rights, by empowering individuals to realize their own reproductive ideals and broader well-being. Because in the end, how we see the world’s population is, quite literally, how we see ourselves. Who are we? Who do we want to be? The future of humanity can be one of the infinite possibilities; the choice belongs to us.